100th

MP

|

THE

100th

MONKEY

PRESS |

|

|

|

Limited Editions by Aleister Crowley & Victor B. Neuburg |

|

Bibliographies |

|

Download Texts

»

Aleister

Crowley

WANTED !!NEW!!

|

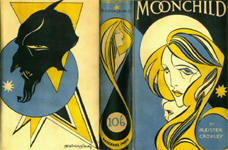

|

MOONCHILD |

|

»» Download Text «« |

Image Thumbnails |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Title: |

Moonchild. A Prologue. |

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Variations: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Publisher: |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Printer: |

The Crypt House Press Limited, Gloucester and London.3 |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Published At: |

London.1 |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Date: |

25 September 1929.4 |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Edition: |

1st Edition. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Pages: |

viii + 336.2 |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Price: |

Priced at ten shillings and sixpence.3 |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Remarks: |

The original working title of this novel was The Butterfly-Net.7 A "Note on Moonchild" penned by Grady McMurtry gives some insight into the possible real characters on which Crowley based the fictional characters in this novel. A copy was presented to Cora Germer with an inscription by Crowley which read “To Cora Germer not merely because she is probably what that Moonchild grew up to be; but because she is rather a nice kid. Aleister Crowley. An. I 4 Sun in 3° Libra.” (Given to Sascha Germer).5 |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Pagination:2 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Contents: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Author’s Working Versions: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Other Known Editions: |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bibliographic Sources: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Comments by Aleister Crowley: |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Reviews: |

Moonchild By Aleister Crowley. (The Mandrake Press, 10s. 6d.) We have an unusual measure of genius in the phrases born of the author’s fancy, but the mystical in the pages of “Moonchild” appears to be overweight, if clever. Mr. Crowley’s effort appears to be to work into the chapters a full, true and particular description of the magical operation by which the spirit of the moon was invoked into the being of an expectant mother, despite the machinations of the Black Lodge of rival magicians. Plots and counter-plots are provided in abundance; there are many nationalities concerned, and a “certain Abbey” in Sicily is chosen for what the author calls the great experiment. “Moonchild” was written a dozen years ago, “during such leisure as my efforts to bring America into the war on our side allowed me.” And, asks the author, “Need I add that, as the book itself demonstrates beyond all doubt, all persons and incidents are purely the figment of a disordered imagination?” There is, the reviewer might add, the pen of a ready writer; the alert and spontaneous brain of the unbaiting thinker, and the action of a man who is accustomed to have thoughts translated into words and carried into deeds. Here are talks on marriage, on alcohol and one knows what besides, and scarcely upon what pegs the talk are hanging; these are quotations from Scripture and from Byron and Tolstoi, and even George Sand, Chopin, Maximilian, and that Salt lake City notoriety - Joseph Smith. One Cyril Grey is an oft-recurring figure in the story. He is the King Charles head of the whole narrative. But Madame Blavatsky and Theosophy and Christian Science are worked into the fabric which runs out to a full fabric in which war is made up of the web and weft. Now we have two chapters in which names are more familiar, some that are revered, some abhorred. We get an idea like this : All Europe will be serene and stand for years to come. But the new generation will fear neither poverty nor death. They will fear weakness, they will fear dishonour. Foch. Von Kluck, Cripps, Joffre, and the then Crown Prince, come into the picture; there is some preaching of foreign affairs; some talk of espionage; some of promotions and of what the Crown Prince was expected to do; and a graphic picture of the retreat from Mons. But that is unmatched in history, says Crowley, and is known and has been read of all men. —The Sheffield Independent. 16 October 1929. ______________________________

Moonchild. By Aleister Crowley. Mandrake Press. 10s 6d.net. A sub-title to “Moonchild” are the words “A Prologue.” We take this to mean that Mr. Aleister Crowley will produce a sequel to this amazing mixture of black and white magic. Much of the book is frankly revolting in it’s details. If such abominations are performed they are hardly fit subject for a work of fiction. The tale is, briefly, concerned with the efforts of white magicians to secure the entrance of a spirit of the moon into an expectant mother; and the efforts of black magicians to defeat the white. The moonchild is born, and forthwith disappears from the story, which then finishes during the war. In this the white magicians reveal the German General Staff plans to Foch while the British Army is retreating from Mons. The whole atmosphere of the story is unreal and unpleasant. —The Morning Post, 25 October 1929. ______________________________

The average novel reader would be dazed by Aleister Crowley’s “Moonchild” (London: The Mandrake Press, 10s 6d). The brilliantly original fancy that leaps and coruscates in this fantastical romance is directed by an acute intelligence and used with a craft not perhaps equaled outside the superlative whimsies of Anatole France. The story of “Moonchild” is so much moonshine. It is the substantial interest of its background that arrests, dazzles, and provokes. “Moonchild” is a literary curio. Collectors of bizarre bric-a-brac should secure it. —The Courier and Advertiser, 7 November 1929. ______________________________

Moonchild, By Aleister Crowley. Mandrake Press: 10s 6d. “Moonchild” is one of the most extraordinary fantastic yet attractive novels we have read. A twice-divorced “widow” falls in love with Cyril Grey, who turns out to be a magician and member of an altogether saintly order of thaumaturgists. It is desired that Grey’s child by this woman shall be fashioned by pre-natal influences that it will grow up to be a great regenerator of mankind. A hostile corps of magicians set themselves to frustrate this experiment and a battle of demonology rages round the Neapolitan villa where the honeymoon couple have their quarters. The upshot need not be disclosed, but it’s significance is rather more obscure than that of the body of the story. The charm of “Moonchild” lies in the telling. We are constantly reminded of the moods of Anatole France and the methods of Rabelais. From extensive dissertations on magic and spiritualism we are suddenly switched into humour that is sometimes normal, sometimes sardonic. From a glimpse into the blackest mysteries of Hecate we are transferred to a wonderful white vision of the poets. From the trivialities of peace we emerge into the horrors of the Great War. “Moonchild” is not more fantastic than a thorough going “thriller”, but it is also a satire and an allegory, full of disorder and genius. —The Aberdeen Press Journal, 28 October 1929. ______________________________

Moonchild. A Prologue. By Aleister Crowley. 335pp. Mandrake Press 10s 6d. This curious novel was written some twelve years ago but appears now apparently for the first time and without additions or emendations. It will be found interesting more for it’s dabblings in medieval magic, both black and white, than for any merits it possesses as a novel, for the motives equally with the methods of it’s dramatis personae, are too distant from the common experience of humanity to attract of themselves. The story is that of a group of white magicians who go “soul fishing in the fourth dimension,” seeking to draw a spirit of the moon into the body of an expectant mother, and of the plots of a rival black lodge to set their plan awry. There is a good deal of ceremony, some of it of an extremely unpleasant nature, described at length, and a defence of magic which is evidently intended to be taken seriously. But the tale is itself in sense, though not wholly, a hoax, and no single intellectual level is long maintained. At times, as in the interview between Douglas, the Black Magician, and “Doc” Butcher, an American aspirant, it descends to pure farce. Mr. Crowley is clever, and has literary skill, but here, as in earlier writings, he identifies himself too completely with the actuality of magical experience to be acceptable to the less confident reader. —The Times Literary Supplement, 7 November 1929. ______________________________

Possibly the author may know what this nonsense is all about. —The New Statesman, 4 November 1929. ______________________________

I had no idea that Mr. Crowley was one of the “most mysterious” of living writers, or even that he was mysterious. What does it mean anyway? That he writes mystery novels? That it is a mystery why he writes novels? That no one knows who he is? Or what? —The New Age, 7 November 1929. ______________________________

Two books have come to hand that are in striking contrast. In one, entitled “Moonchild,” we have an example of the complicated, turgid, esoteric writing—the kind that reaches out for the effect that is aimed at by the futuristic painter, in which he gets beyond the infinite—or believes he does. In the other, “Carl and Anna,” a translation from the German, is the simplification of language to perfection. “Moonchild” is difficult to understand. You read words, words, words—mystic references, invented oddities, and peculiar actions, until the confusion is worse confounded, and you get tired of endeavouring to find out what the author is driving at. “Carl and Anna” is one of those plain stories that appear to have been sifted and polished until not one superfluous word is left. One is carried through the first in curiosity to know what strange thing will be said next, while the second holds the interest by the sheer intensity of the dramatic story being told. “Moonchild” is a tale of a “magickal” operation by which a spirit of the moon is invoked into the being of an expectant mother and is full of passages of romance and poetic meanderings in anything but a lucid style. “Carl and Anna” is of a woman left alone when her husband went to the war; of his companion in the prison camp, who is his counterpart in appearance, becoming so saturated with the husband’s talk of his wife that when he escapes he impersonates the husband, and, though detected by the woman, is accepted by her as such. —The Sydney Morning Herald, 6 June 1930. ______________________________

The attack in the Press which led to Aleister Crowley’s first novel “The Diary of a Drug Fiend” will be recalled by many readers. Here is another story more fascinating than daring, which could only have come from the brilliant pen of this amazing writer. It describes a magical operation by which a spirit of the moon is inculcated into the being of an expectant mother despite the attempted preventions of rival magicians. Sicily is chosen as the centre for the great climax of the story. There are weird happenings at a séance with restless fingers “moving and twisting in uncanny shapes.” Articles upon the table “hop, skip and dance like autumn leaves in a whirlwind.” The story is strange and entrancing, and fully in keeping with the striking personality of the author. —The Nottingham Journal, 8 November 1929. ______________________________

This is hardly a book that will appeal to the general public, though the general public reads and will continue to read books that are much less clever and amusing. But “The Moonchild” make too great a demand upon the intelligence, and, besides, it assumes a knowledge (which two centuries ago was general) of the main principles of astrology and magic. People will believe in spiritualism which insults their intelligence, while they prove that they are intelligent by refusing to consider the much stronger evidence (so far as it goes) for magic and astrology. But the author has an enemy to castigate, a writer well known to students of occult literature. He is pilloried in this book under the name of Edwin Arthwait. This voluminous and murky writer, who is forever fluttering upon the edge of making a definite statement but never making it, because he has never made up his mind as to what he really wishes to say, is satirised and parodied with immense gusto. But the parody will appeal only to those readers who have sounded the hollow caverns of the original. The book is a story of a young Englishman who wished by means of magic, not the black magic of the sorcerer, but the philosophic magic of the Neo-Platonists, to produce a child who shall be as completely as possible under the astrological influence of the moon. He goes off ostensibly for this purpose with a young woman to Naples. But he has the usual enemies, the members of a Black Lodge of Sorcerers, whose object is to spoil the experiment and get hold of the young woman. The story of how he tries to elude them, succeeds for the time, is pursued, besieged, and confounds his enemies, only to lose the young woman in the end, forms an entertaining tale. At the last it turns out that the real child and its mother were not the unborn child and its mother who was decoyed away from him, but quite another young woman who had gone off somewhere else to have her child before he went off to Naples.. In the latter part of the book there is a really bloodcurdling chapter or two about the Black Lodge of Sorcerers in Paris, not to be commended to persons of weak nerves, but very good for all that. The hero ends up by joining the British Army during the retreat from Mons. The unlucky “Edwin Arthwait” is not the only contemporary or lately deceased person upon whom the author employs his powers of sarcasm; and it is quite amusing, though sometimes a little too easy, to pick out the originals. A book as clever as this is about international crooks would have sold by the thousand. One doesn’t know how many will be sold of “Moonchild,” but the people who buy it, and who can appreciate its wit and see the point of a reference, will not feel that they have wasted their half-guinea. —The Northern Whig and Belfast Post, 22 October 1929. |

|||||||||||||||||||