100th

MP

|

THE

100th

MONKEY

PRESS |

|

|

|

Limited Editions by Aleister Crowley & Victor B. Neuburg |

|

Bibliographies |

|

Download Texts

»

Aleister

Crowley

WANTED !!NEW!!

|

|

AMBERGRIS |

|

»» Download Text «« |

Image Thumbnails |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Title: |

Ambergris. A Selection from the Poems of Aleister Crowley. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Variations: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Publisher: |

Elkin Matthews, Vigo Street.3 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Printer: |

Strangeways Printers, Great Tower Street, Cambridge Circus, W. C.2 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Published At: |

London.3 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Date: |

circa March 1910. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Edition: |

1st Edition. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pages: |

viii + 198 + 2 pages of advertisements.1 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Price: |

Priced at 3 shillings and sixpence.2 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Remarks: |

Tipped in as a frontispiece is a photogravure of Aleister Crowley, New York, 1906.1 Some copies have a erratum slip stating “Mr Crowley's Books are to be obtained at the office of the 'Equinox.' 124 Victoria Street, London, S.W.” tipped in facing p. 198.4 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pagination:1 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contents: |

From ‘The Tale of Archais’ - Song - In Hollow Stones, Scawfell From ‘Songs of the Spirit’ - The Goad - Astrology From ‘Jephthah’ - Chorus of Maidens From ‘Mysteries’ - De Profundis - Beside the River - Perdurabo - In the Woods with Shelley From ‘The Fatal Force’ - Chorus - Chorus - Chorus From ‘The Temple of the Holy Ghost’ - The May Queen - The Reaper - The Palace of the World - The Rosicrucian - The Athanor - A Death in Thessaly From ‘Tannhäuser’ - Shepherd Boys - Tannhäuser’s Song From ‘Oracles’ - The Hermit’s Hymn to Solitude - On Waikiki Beach From ‘Alice: An Adultery’ - Margaret - Red Poppy - Alice From ‘The Argonauts’ - Chorus of Shipbuillders - At Waikiki - The Harbour - Vera Cruz - The Song of the Siren Leucosia - Hong Kong Harbour - At Prome From ‘The Star and the Garter’ - Song - Song Rosa Mundi Other Love Songs - Dora - Norah - Edith - Rose - Eileen - Helene From ‘Gargoyles’ - Song - Said - Prayer - The King-Ghost From ‘Rodin in Rime’ - Tete de femme (musee du Luxembourg) - Reveil d’Adonis - Acrobates - Faunesse - Balzac From ‘Orpheus’ - The Hours - Autumn - Invocation of Hecate - The Regaining of Eurydice - The Maenads Invoke Dionysus - Orpheus Invokes the Lords of Khem - The Star-Goddess Sings of Orpheus Dead |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Author’s Working Versions: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

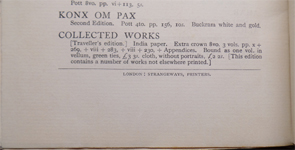

Other Known Editions: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bibliographic Sources: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Comments by Aleister Crowley: |

In response to a widely-spread lack of interest in my writings, I have consented to publish a small and unrepresentative selection from the same. With characteristic cunning I have not included any poems published later than the Third Volume of my Collected Works. The selection has been made by a committee of seven competent persons, sitting separately. Only those poems have been included which obtained a majority vote. This volume, thus almost ostentatiously democratic, is therefore now submitted to the British Public with the fullest confidence that it will be received with exactly the same amount of acclamation as that to which I have become accustomed. — Preface, Ambergris, Elkin Mathews, 1910. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Reviews: |

Judging from the elaborate sarcasm of his preface to “Ambergris,” Mr. Aleister Crowley would seem to be rather hurt in his mind that the British public should have mostly ignored his previously published writings. But Mr. Crowley is by no means the only contemporary poet who is well worth reading and is yet not read. It would, indeed, be rather surprising if Mr. Crowley’s books had created much stir in the reading world. For one thing, he deals very largely in mystical and esoteric doctrines, of the kind likely to repel the majority of downright Englishmen as powerfully as they have attracted his few enthusiastic admirers. These doctrines, too, are often expressed symbolically figured by the great names of ancient religions. The average man does not much mind meeting with a miscellaneous host of heathen gods and demigods in poetry; but when he is forced to feel that these gods and demigods are all intensely alive in Mr. Crowley’s mind, the focal points, as it were, of doctrines which Mr. Crowley passionately holds for eternal and almighty truths, then the average man is apt to sheer off from such poetry with dubious and rather scared looks. Nevertheless, in spite of this, Mr. Crowley’s name, if only as a vague rumour, has become known to most of those who are looking for a great contemporary poet. And now, for the better information of such people, we have a selection from his works (some of which are not very obtainable), presented in a shape by no means formidable to the lean purse; and the poorest poetry-lover can now find out what sort of a poet Mr. Aleister Crowley really is. He certainly is worth reading—not so much for the doctrines, some noble, some queer, which he inculcates, as for the poetry he sometimes manages to make out of them. The man who loves poetry wisely is willing to accept from a poet any creed or doctrine he likes to air, from the materialism of Lucretius to the mysticism of Blake, provided always that he makes poetry of it. Much of Mr. Crowley’s dogmatic poetry is mere mouthing, the primal obscurity of his theme still more darkened by studied eccentricity of image and extravagance of diction. The emulation of Swinburne’s manner is at times too obvious to be satisfactory; and Shelley comes in for some sincere flattery. But there are poems in “Ambergris” which are all Mr. Crowley’s own, fine poems in which (to quote from one of them),

There is music and terrible light And the violent song of the seas;

intellectual passions wedded to melody that will not easily be forgotten. There are plenty of such pregnant sayings as this:

Mere love is as nought To the love that is Thought, And idea is more than event.

There are poems, such as “The Rosicrucian,” which are daring experiments in philosophy and in psychological construction alike. This is a noble verse:

No man hath seen beneath my brows Eternity’s exultant house. No man hath noted in my brain The knowledge of my mystic spouse. I watch the centuries wax and wane.

The descriptive poems, especially those descriptive of the tropics, are excellent of their kind; but the finest poem in the book is undoubtedly an “Invocation to Hectate.” A large idea, rigorous verbal craftsmanship, and a spacious music, combine to make that one of the most notable magical poems ever written. Here is a snatch of it:

I shall consummate The awful act of worship. O renowned Fear upon earth, and fear in hell, and black Fear in the sky beyond Fate! I hear the whining of thy wolves! I hear The howling of the hounds about thy form. Who comest in the terror of thy storm, And night falls faster, ere thine eyes appear Glittering through the mist.

—The Daily News, 16 May 1910. ______________________________

It is perhaps not uncharacteristic of the poet of these verses that he should give them a title which has really but little connection with them. A certain perverseness or wilfulness is manifest in much of his work, and surprise and paradox are effects which seem dear to him. For these poems are of Grecian rather than of Arabian or Persian origin, and the fragrance of Ambergris is a much lighter and more spiritual thing than the rich and arrogant perfume of Arabia. Maybe Mr. Crowley so entitled his poems, as one christens a child Rose or Wilhelmina or Théophile, without any descriptive or moral intentions at the back of one's mind. Maybe, he just fell a victim to the charms of a pretty word, as any susceptible poet might, and made her forthwith the doorkeeper of his poetic seraglio. Perhaps it was not worth writing, since he who can afford to be vain can afford to forego the demands of his vanity, yet there it is, and of itself it would make one wonder if the author of Ambergris and some thirty other volumes had any right to be piqued because he is not as well known and as well acknowledged as he would like to be. A glance through his press notices convinces one that there is at least a chance that he has such a right He has been roundly condemned, treated to impertinence, and in some cases extravagantly praised, but no one seems to have given him that deadly kind of appreciation which is the lazy critic's heart-felt thanks that there is nothing to criticise. Nobody has called him a classical poet, or "one who is preserving the best traditions of our noble heritage of song," or assured him that he is " of the true succession," or anything of that kind. This shows that there is, at least, a fair chance of his being a good poet, though of course it does not prove it, for it is possible for a man to be a very bad poet and yet not be praised by the Weary Willies of academic criticism. A first glance at Ambergris shows Mr. Aleister Crowley as perhaps the most passionate disciple poet ever had. Such imitation of Swinburne's manner, as is revealed in most of his early work, could only have been born of the strongest love for the champing colourous rhythms of the Victorian. By itself, for the passion which inspired it, it commands respect. But there is too much of such work included here. It prevents access to what is strong and personal in the book. It shows a passion which was one day bound to define itself in letters of original flame. It prophesied, but a sceptical world only believes such when they come true. That something has come true in our poet's case will be admitted, I think, on reading Alice:

The stars are hidden in dark and mist, The moon and sun are dead, Because my love has caught and kissed My body in her bed. No light may shine this happy night— Unless my Alice be the light.

This night—O never dawn shall crest The world of wakening, Because my lover has my breast On hers for dawn and spring. This night shall never be withdrawn— Unless my Alice be the dawn.

Mr. Crowley is very successful in this kind of thing. These love-songs of his have a wonderful ardour, an almost Sapphic fury. They flash and shine with images that are like little streaks of flame. Sometimes, though, he is more delicate and more ethereal as in the following verse from Red Poppy:

One kiss like snow to slip Cool fragrance from thy lip To melt on mine; One kiss, a white-sail ship To laugh and leap and dip

Her brows divine; With love of a sweet saint Stolen like a sacrament In the night's shrine.

The verse with which the book opens is a beautiful stanza. It has all the hard brilliance and the lustre which are characteristic of the writer's work. The opening picture breaks on the senses like a shaft of sudden sunshine.

Ere the grape of joy is golden With the summer and the sun, Ere the maidens unbeholden Gather one by one, To the vineyard comes the shower, No sweet rain to fresh the flower, But the thunder rain that cleaves, Rends and ruins tender leaves.

Among many things that occur to one in reading Mr. Crowley's verses is their singular disseverance from the things of the day, their entire lack of what is called "the modern note" in poetry. Of course such a devotion as in his early work he gave to Swinburne, Browning, and Shelley would not allow him to serve other masters. We must think that he deliberately shut his eyes to the writings of the intimate, romantic, impressionist school, or else how could so susceptible an artist have escaped its infection? Another thing that is apparent in this poet's work, despite the cumulative effect of his poems, is the fitfulness of his inspiration. His gift, splendid as it appears at times, is unique and occasional rather than rich and sustained. A journey through the garden of the poet's verses has all the excitement and the drawbacks of making one's way by means of the illumination of lightning. There is a lot of darkness to a small proportion of extreme brilliance, though, perhaps, as with all rare and superfine things, this is necessarily the case. It is their price I will now take some single images or metaphors from the poems and place them by themselves. It is in these things and by their quality that the poet is shown. Is this not natural, for what is art after all but one vain adjective for ever seeking its impossible noun? What is all poetry but one imperfect metaphor, an analogy made with one of the comparisons only half guessed at through Eternity's veil? Observe the tremendous compression of thought in the lines, where the poet speaks of old love buried and seemingly forgot, rising up and breaking out from

. . . the untrusty coffin of the mind.

Again, what a delightful picture is suggested in the

winged ardour of the stately ships.

How closely those two words winged and ardour are bound! Welded in the original passion of creation, they hold their idea with a noble security. Criticism cannot sunder them. Beautiful, too, I fancy are the lines:

To some impossible diadem of dawn.

The trampling of his (the sun's) horses heard as wind.

My empire changes not with time. Men's Kingdoms cadent as a rime Move me as waves that rise and fall.

Of poetry Mr. Crowley says:

Thou art an Aphrodite; from the foam Of golden grape and red thou risest up Immaculate; Thou hast an ebon comb Of shade and silence, and a jasper cup. . . .

This, of a lady:

So grave and delicate and tall— Shall laughter never sweep Like a moss-guarded waterfall, Across her ivory sleep?

There are some noble and vigorous images scattered among Mr. Crowley's verses, whose invention alone marks him out as no inconsiderable poet. For the rest, great metrical force, rhythms so violent as almost sometimes to exhaust themselves, and, in some of the later work, a curious employment in his philosophy of paradox—that Mr. Facing-Both-Ways of literary effects. I will end on a lighter note, and quote the beautiful and tender song from The Star and the Garter. Is there not in it a reminiscence of all the beauty of our lives that has passed like water through the helpless senses? Is there not a certain very fairy and frosty note in this song, such as—to be ridiculously fanciful—an elf might make with a rose-leaf and a fretted mandoline of hoar-frost, something cold, yet warm at heart, like a very lovely yet unreachable lady, the lovelier for the pedestal of snows on which she is set?

Make me a roseleaf with your mouth, To some far garden of the South, The herald of our happening there!

Fragrant, caressing, steals the breeze; Curls into kisses on your lips:— I know interminable seas, Winged ardour of the stately ships. —The English Review, December 1910 by Edward Storer (An alias of Aleister Crowley?). ______________________________

This book appeared in the summer of 1910. Since that time Mr. Crowley has come into greater prominence, not so much as Frater “Perdurabo,” but more as the writer of some sound prose and fine commentary criticism. He is outliving his inane attempts to reform the world by false magic, and his truer magic, his poetry, is gaining in influence. The present collection is a good and for the most part pleasing one, but we are quite sure the committee of which each member sat separately for the making of this selection did not include any maiden aunts. If so, the piece, “The Reaper,” would not have been reprinted, nor “The May Queen.” Parents of impressionable young ladies, please note. “The Goad” is a fine and inspiring piece, pleasantly reminiscent of Keats, and the first song is a splendid piece of word music. —The Poetry Review, January-June 1914. ______________________________

“In response to a widely-spread lack of interest in my writings, I have consented to publish a small and unrepresentative selection from the same,” says Mr. Aleister Crowley in the preface to “Ambergris” (Elkin Mathews). I surmise that one reason for the widely-spread lack of interest in Mr. Crowley’s admirable verse has been the price of it. Thus “Rosa Mundi,” a quarto pamphlet of seventeen pages, is sold at 16s. Perhaps I ought to say it is offered. Happily “Rosa Mundi” is included in “Ambergris,” and a fine poem it is. Mr. Crowley is one of the principal poets now writing. Yet if any mandarin had to write an article on our chief living poets he would assuredly not mention Mr. Crowley. I doubt if he would mention Lord Alfred Douglas, who has, I imagine, produced immortal things. On the other hand he would not fail to speak at length about Mr. Laurence Binyon, with extracts! Why are Mandarins thus? —The New Age, 13 April, 1911. ______________________________

We have lately received this book of poems by the talented author, Mr. Aleister Crowley, the high-priest of a cult as sacred as any which the Sufis cherish in their perfumed gardens, and having glanced in our usual casual manner at the contents, we were immediately drawn to peruse the whole with avidity. Nor did we regret our labours, for, suffering from one of our slight attacks of depression, the optimistic spirit which pervades the poetry of this author left us in an unusually contented state of mind. Here is the conclusion of a poem called Astrology:—

So shalt thou conquer Space, and lastly climb The walls of Time, And by the golden path the great have trod Reach up to God!

Yet are we not surfeited with this spirit, for the author shows himself not altogether unsympathetic with those who sometimes see a darker side. He can touch with a hand that soothes without repelling those subtle wrinkles of the brain which draw us into the depths without our being able to analyse them. Perhaps it is worth while here to quote the whole of the last stanza from a Song taken from The Tale of Archais:—

All the subtle airs are proven False at dewfall; at the dawn Sin and sorrow, interwoven, Like a veil are drawn Over love and all delight. Grey desires invade the white. Love and life are but a span; Woe is me! and woe is man!

This seemed to us to carry some of the spirit of Swinburne and reminded us of The Forsaken Garden, especially the stanza beginning:—

Here death may deal not again forever.

The author assumes a certain mock modesty in the preface, but we do not think he need fear any "widely-spread lack of interest." The book contains between fifty and sixty poems, all with an exuberant style and showing great technical skill in metre. The lines flow in rhythmical waves and one is carried along by the sound as well as the sense. Space compels us to close with the following stanza, which carries with it a haunting memory:—

She laughs in wordless swift desire A soft Thalassian tune; Her eyelids glimmer with the fire That animates the moon; Her chaste lips flame, as flames aspire Of poppies in mid-June.

PERCIVAL ROBERTS. —The Occult Review, August 1910. ______________________________

“Ambergris, a Selection from the Poems of Aleister Crowley” (Elkin Mathews) is the most interesting volume of new English verse seen this year. Crowley was met years ago in the “English Critical Review,” and has occurred here and there since, seeming always extraordinary. He is extraordinary—in is work, in the fine portrait prefixed to his work, and in his preface, which runs thus:—

“In response to a widely spread lack of interest in my writings, I have consented to publish a small and unrepresentative selection from the same. With characteristic cunning I have not included any poems published later than the Third Volume of my Collected Works. “The selection has been made by a committee of seven competent persons, sitting separately. Only those poems have been included which obtained a majority vote. “This volume, thus almost ostentatiously democratic, is therefore now submitted to the British public with the fullest confidence that it will be received with exactly the same amount of acclamation as that to which I have become accustomed.”

The little volume of 200 pages is commended as a pleasure to every amateur of poetry in New Zealand. One does not remember any verse so plastic as some in the earlier pages of “Ambergris.” Crowley writes shapes, beautiful shapes, beautiful coloured shapes like chryselephantine statuettes. Readers of verse know that there is ear-poetry and eye-poetry, poetry that sounds well and looks ill, and poetry that looks well and sounds ill. Crowley makes an unusual appeal both to eye and to ear. In particular, he has a gift of good beginnings, he attacks admirably:—

Rain, rain, in May. The river sadly flows. . .

Sing, happy nightingale, sing; Past is the season of weeping. . .

In middle music of Apollo’s corn She stood, the reaper, challenging a kiss. . .

She fades as starlight on the stream, As dewfall in the dell. . .

If form were all! Crowley fails in emotion. His verse does not yield that ecstasy that adds the last drop to the brimming vase. He is always evident, never ineffable. Nor, although original, is he highly, compellingly original; he does not lead us to unfooted fields of dream; at most he finds a new path in the familiar territory. Yet to call him “minor” is to do him injustice; he has the voice, though not the great imagination; and his skill with lines and rhymes, words and phrases, is more than craft. Crowley has travelled, and writes harmonious stanzas for Hawaii, for Egypt, even for Hong-Kong. Perhaps after Verhaeren (for we catch an echo here and there) he cries:—

To sea! Before us leap the waves; The wild white combers follow. Invoke, ye melancholy slaves, The morning of Apollo! . . .

The ship is trim; to sea! to sea! Take life in either hand. Crush out its wine for you and me, And drink, and understand!

There are many Shakesperian touches in Crowley, and not so many Shakesperian lapses. If you stress the lapses, he gives a line for maltreating:

Smite! but I must sing on. . .

What a motto for our bards, ifay! Accept Crowley of refuse him. He brings his own atmosphere, and captivates you, there is such a tide of life in him. And for closing, let the Star-Goddess sing a stanza of Orpheus dead—and risen:—

For brighter from age to age The weary old world shall renew It’s life at the lips of the sage. Its love at the lips of the dew. With kisses and tears The return of the years Is sure as the starlight is true. . .

There is one that hath sought me and found me In the heart of the sand and the snow; He hath caught me, and held me, and bound me. In the lands where no flower may grow, His voice is a spell Hath enchanted me well! I am his, did I will it or no. . . —The Bookfellow, 17 December 1910. ______________________________

Ambergris (Elkin Mathews, 3s. 6d.) is the title of a selection from the poems of Mr. Aleister Crowley, who when he is not occupied with Hermetic Orders of Golden Dawns and other magical mysteries, contrived to write an astonishing amount of verse, which is subsequently published at process far beyond the purses of the vulgar. Mr. Crowley is a very interesting survival, combining a mediaeval imagination with a wit which is essentially fin de siècle. In his preface to the present volume, he says: “In response to a widely-spread lack of interest in my writings, I have consented to publish a small and unrepresentative selection from the same . . . with the fullest confidence that it will be received with exactly the same amount of acclamation as that to which I have become accustomed.” At the risk of incurring the wrath of the whole Macgregor clan, we venture to think that Mr. Crowley’s confidence is not misplaced. The verses, as full of colour as a painting by Matisse, are admirable as a short cut to euthanasia. —The Labour Leader, 24 June 1910. ______________________________

Mr. Aleister Crowley’s “Ambergris” has little of Headlam’s punctilious restraint and nothing like Wilde’s craft and dexterity. Mr. Crowley is in a sense hors concours. This is his twenty-ninth published volume; none the less it is only, as he describes it in his ultra-modern preface, “an unrepresentative selection”—a remark that cannot be else than intended to silence his critics. —The Bookman, November 1910. ______________________________

Mr. Aleister Crowley has some considerable fame of an esoteric kind; but he is far too good a poet for a coterie to possess, and this selection from his poems, even though it be “small and unrepresentative” (as the author’s preface asserts), is a very welcome publication. The poems printed in “Ambergris” are, at any rate, sufficient to show anyone who has the true, unquenchable thirst for poetry that Mr. Crowley’s song is something remarkable, both for its inner and its outer music—its spacious and, at times, magnificent imagery, its subtle use of verbal suggestion, and its ringing metre and unusually fine stanza-construction. The last-named is possibly the most potent element in the beauty of Mr. Crowley’s poetry; it certainly makes the stanzaic poems hold his occasionally violent and extravagant diction better than the other poems, since torrents of words must flow through moulds of rigorous form or risk wasting half their strength. There is no mistaking the prosodic skill in these stanzas from a Chorus:—

“In the ways of the North and the South, Whence the dark and the dayspring are drawn, We pass with the song of the mouth Of the notable Lord of the Dawn. Unto Ra, the desire of the East, let the clamouring of singing proclaim The fire of his name!”

“In the ways of the depth and the height, Where the multitude stars are at ease, This is music and terrible night, And the violent song of the seas. Unto Mou, the most powerful Lord of the South, let out worship declare

Him Lord of the Air!” And, for another and contrasted sample of his stanza-construction, the first verse of a descriptive poem of “Hong Kong Harbor” will show his use of a quieter music:—

“Over a sea like stained glass At sunset like a chrysopras:— Our smooth-oared vessel over-rides Crimson and green and purple tides. Between the rocky isles we pass, And greener islets gay with grass; Between the over-arching sides Our pinnacle glides.”

But the finest stanza-form in “Ambergris” is the long elaborate one used for the admirable “Invocation of Hecate,” in every way perhaps the most remarkable poem here given, from which we shall have to quote when we come to consider the intellectual qualities of Mr. Crowley’s verse. It should be mentioned, however, while we are still on this matter, that Mr. Crowley can also work his own music into stanza-forms that have long ago been brought to famous perfection, as Sapphics and the Rubaiyat-verse—a much more difficult task, on the whole, than the invention of new forms. His Omar quatrain follows Swinburne’s “Laus Veneris” rather than FitzGerald, the stanzas being linked in couples by rhyme in the third line; and the Sapphics betray the same modifying influence. The Swinburnesque energy, too, of the anapest choric stanzas quoted above is pretty obvious; and, indeed, it may be said that the spirit of Swinburne has helped to compose a good deal of the passionate, clangourous poetry in “Ambergris,” working sometimes at the phrasing as well as at the metre. But Swinburne has not had much to do with the content of Mr. Crowley’s poetry. Resemblances to Shelley may be traced in some of his matter; but really the thought, and the emotion of thought, which support this poetry, are entirely and intensely Mr. Crowley’s own. And these, as a rule, are the main things in poetry. By that, of course, we are far from meaning that the value of a poet is measurable by the value to the world of the “message” which fills him. What we do mean, however, is that the worth of a poet depends on the value of his own “message” to himself—provided, of course, that he is genuinely a poet, one who can make music of his thought. Here is a verse, the music of which is enough by itself to prove Mr. Crowley a poet:—

“The sun looks over the memorial hills, The trampling of his horses heard as wind; He leaps and turns, and all his fragrance fills The shade and silence; all the rocks and rills Ring with the triumph of his steed behind.”

A very casual glance at “Ambergris” will convince anyone with understanding eyes that Mr. Crowley is as passionately possessed by his theme as any poet ever has been. This should ensure a constant achievement of notable poetry. But, as a fact, it does not. The achievement varies immensely, from a vague outpouring of syllables to clean-cut, pregnant phrases, and a precise splendor of imagery. Sometimes Mr. Crowley’s failure comes from a desire to strain language beyond its capabilities, which leads him further to use all possible and impossible forms of speech. For instance, he will write these daring and excellent lines:—

“For, know! The moon is not the moon until She hath the knowledge to fulfil Her music, till she know herself the moon.”

And then he follows them up with this, which is, to be plain, simply bungling:—

“The stone unhewn. Foursquare, the sphere of human hands immune. Was not yet chosen for the corner-piece And keystone of the Royal Arch of Sex; Unsolved the ultimate x.”

The fault of such lapses does not really lie in any aberration of poetic power. It is merely that Mr. Crowley is endeavoring to sing what is unsingable. This is the penalty that mysticism must always pay, sooner or later; and mysticism is Mr. Crowley’s theme. Precisely what species of mysticism he professes, or rather, for all mysticisms are fundamentally the same, into what shape of metaphors and symbols Mr. Crowley has fashioned his mysticism, we need not stop to determine. Its importance to him is immense; it is the hinge of his whole thought. To us, its importance is simply that it carries him often into excellent poetry. The main intellectual passions which move him will be familiar to all who have studied writers tinged or impregnated with mystical and transcendental thought:—

“For secret symbols on my brow, And secret thoughts within, Compel eternity to Now, Draw the Infinite within. Light is extended. I and Thou Are as they had not been.”

“The Palace of the World” and “The Rosicrucian” are two poems in which the fundamental yearnings of mysticism find expression which is simple and intelligible as well as vehement and beautiful. As for the details of Mr. Crowley’s creed, they are exceedingly eclectic, not to say conglomerate. The Buddhistic flavor, for instance, in this striking verse is unmistakable:—

“Still on the mystic Tree of Life My soul is crucified; Still strikes the sacrificial knife Where lurks some serpent-eyes Fear, passion, or man’s deadly wife Desire, the suicide.”

For his mystical calendar, Egypt supplies him with a troop of deities, Ra and Roum and Mou, no longer “brutish gods of the Nile,” but “notable lords” and “most powerful lords”; Greece supplies him with Orpheus; “and many more too long.” In general. As long as Mr. Crowley’s poetry is working through his mythological machinery, it is, though somewhat baffling to the mind unlearned in strange faiths, at a high pitch of excellence; because it is constrained and the thought kept ordered. There is also much other systematic symbolism, which does the same office; the spirits and virtues of precious stones, for example:—

“Lapis-lazuli for love And ruby for enormous force.

But mysticism is seldom content with symbolic or other restriction, though some kind of restriction of thought is absolutely essential to poetry. There are vague doctrines in Mr. Crowley’s mind which are probably quite irreducible even by way of suggestion, to terms which originate in sensuous and reasonable experience; and a determination to express these super-subtle thought too often results in nothing but an incondite mass of language. But sometimes, as in an extraordinary poem called “The Reaper,” Mr. Crowley surprisingly succeeds in snaring, as it were, into a haze of poetry some of those unappointed fires of the soul which have as yet found no place in the recognized thoughts and emotions of man, of which few are even conscious—those fires which are, ultimately, the life of all mysticism. No doubt, however, there will be those who will strongly prefer the poems in “Ambergris” in which verbal beauty is unvexed by philosophy, such as the descriptive poems, or the address of Orpheus to his regained Eurydice, which ends with this fine stanza:—

“The green-hearted hours The winds shall waft roses from uttermost Ind. Our nuptial dowers shall be birds in our bowers, Our couches the delicate heaps of the wind, Where the lily-bloom showers all its light, and the powers Of earth in our twinning are wedded and twinned.”

Nevertheless, we must look for Mr. Crowley’s best work in those poems wherein he is really supported, not merely inflated, by his creed, whatever the creed may be. Then he is kept safe from lapses into triviality and bombast, to both of which faults he is certainly liable. Perhaps the most remarkable instance of the support given him by his mysticism is in the exceedingly fine “Invocation of Hecate,” already mentioned. This is something more than an exercise in literary magic, like Horace’s or Ben Johnson’s, admirable as poetry though the Canidia Epode and the Masque of Queens are. But Mr. Crowley’s “invocation” seems earnest with belief; not necessarily, of course, with a belief in Hecate herself, but in some power, in the mind or in the spiritual universe, which the dreaded name of Hecate dimly shadows forth. This is the second stanza of the poem:—

“Here where the band of Ocean breaks the road Black-trodden, deeply-stooping, to the abyss, I shall salute thee with the nameless kiss Pronounced toward the uttermost abode Of thy supreme desire. I shall illume the fire Whence thy wild stryges shall obey the lyre, Whence thy Lemurs shall gather and spring round, Girdling me in the sad funereal ground With faces turned back, My face averted! I shall consummate The awful act of worship, O renowned Fear upon earth, and fear in hell, and black Fear in the sky beyond Fate!”

Enough has been said to show that Mr. Aleister Crowley’s “Ambergris” is a volume containing notable poetry. Mr. Crowley’s output has been considerable, and a small book of selections from it can only give a glimpse of his power. Possibly “Ambergris” may arouse sufficient interest in his writing to warrant the publication of his collected works at a price which will not dismay those who are not yet (in Mr. Crowley’s own phrase) “free from gold’s illusion.” —The Nation, 4 June 1910. ______________________________

You may call the poem “Wedded,” and choose some stanzas:

The roses of the world are sad. The water-lilies pale, Because my lover takes her lad Beneath the moonlight veil. No flower may bloom this happy hour— Unless my Alice be the flower

So silent are the thrush, the lark! The nightingale’s at rest, Because my lover loves the dark, And has me in her breast. No song this happy night be heard— Unless my Alice be the bird.

The sea that roared around the house Is fallen from alarms, Because my lover calls me spouse And takes me to her arms. This night no sound of breakers be— Unless my Alice be the kiss.

This night—O never dawn shall crest The world of wakening, Because my lover has my breast On hers for dawn and spring. This night shall never be withdrawn— Unless my Alice be the dawn.

This is extracted from “Ambergris, a selection from the poems of Aleister Crowley” (Elkin Mathews)—the most interesting volume of new English verse seen this year. Crowley was met years ago in “The English Critical Review,” and has occurred here and there since, seeming always extraordinary. He is extraordinary—in his work, in the fine portrait affixed to his work, and in his preface. The little volume of 200 pages, at 3s, 6d, is commended as a pleasure to every amateur of poetry. One does not remember any verse so plastic as some in the earlier pages of “Ambergris.” Crowley writes shapes, beautiful shapes, beautiful coloured shapes like chryselephantine statuettes. All readers of verse know that there is ear-poetry and eye-poetry—poetry that sounds well and looks ill, and poetry that looks well and sound ill. Crowley makes an unusual appeal both to eye and ear. His ivory shapes go singing themselves golden tunes. In particular he has a gift of good beginnings, he attacks admirably. If form were all! Crowley fails in emotion: his verse does not yield that ecstasy that adds the last drop to the brimming vase. He is always evident, never ineffable. Nor, although original, is he highly, compellingly original; he does not lead us to unfooted fields of dream; at most he finds a new path in the familiar territory. Yet to call him “minor” is to do him injustice; he has the voice, though not the great imagination; and his skill with lines and rhymes, words and phrases, is more than craft. He is not “minor” because he has a pulse and a strong opinion; he does not flutter, he soars. Soars best when closest earth: his abstractions are empty: he needs the living model to inspire his art. Then with a puff from swollen Eros:

One kiss, like snow, to sip, Cool fragrance from thy lip To melt on mine; One kiss, a white-sail ship To laugh and leap and dip Her brows divine; One kiss, a sunbeam faint With love of a sweet saint, Stolen like a sacrament In the night’s shrine!

One kiss, like moonlight cold Lighting with floral gold The lake’s low tune; One kiss, one flower to fold, On its own calyx rolled At night, in June! One kiss, like dewfall, drawn A veil o’er leaf and lawn— Mix night, and morn, and dawn, Dew, flower, and moon!

There are many Shakespearian touches in Crowley, and not so many Shakespearian lapses. If you stress the lapses, he gives a line for maltreating—

Smite! but I must sing on. . . What a motto for our Australian bards, ifray!

Accept Crowley or refuse him, he brings his own atmosphere, and captivates you, and finally captures: there is such a tide of life in him, though it does not rise through the finest poetic brain (nor did Shakespeare’s tide). And for closing, let the Star-Goddess sing a stanza of Orpheus dead—and risen.

For brighter from age unto age The weary old world shall renew Its life at the lips of the sage, It’s love at the lips of the dew. With kisses and tears The return of the years Is sure as the starlight is true.

There is one that hath sought me and found me In the heart of the sand and the snow: He hath caught me, and held me, and bound me, In the lands where no flower may grow, His voice is a spell. Hath enchanted me well! I am his, did I will it or no. . . . —The Evening Post, 17 December 1910. ______________________________

. . . There is life and vigour and reality in it,

and a personality sincerely

expressed in spite of

what appears to be willful eccentricities. ______________________________

Ambergris. A Selection of Poems by Aleister Crowley. Elkin Mathews. 3s. 6d. Printed by Strangeways and sons, Great Tower Street, Cambridge Circus, W. C. We don’t like books of selections, and you can’t make a nightingale out of a crow by picking out the least jarring notes. The book is nicely bound and printed—as if that were any excuse! Mr. Crowley, however, must have been surprised to receive a bill of over Six Pounds for “author’s corrections,” as the book was printed from his volume of Collected Works, and the alterations made by his were well within the dozen! [Yes; he was surprised; it was his first—and last—experience of these strange ways.—ED.] If poets are ever going to make themselves heard, they must find some means of breaking down the tradition that they are the easy dupes of every— [Satis.—ED.] Just as a dishonest commercial traveller will sometimes get a job by accepting a low salary, and look for profit to falsifying the accounts of “expenses,” so—— [Here; this will never do.—ED.] We have had fine weather recently in Mesopotamia—[I dare say; but I’m getting suspicious; stop right here.—ED.] All right; don’t be huffy; good-bye! —The Equinox, Volume 1, Number 4, S. Holmes (Aleister Crowley), September 1910. ______________________________

You may call the poem “Wedded,” and choose some stanzas: The roses of the world are sad, The water-lilies pale, Because my lover takes her lad Beneath the moonlight veil. No flower may bloom this happy hour— Unless my Alice be the flower.

So silent are the thrush, the lark! The nightingale’s at rest, Because my lover loves the dark, And has me in her breast. No song this happy be heard— Unless my Alice be the bird.

The sea that roared around the house Is fallen from alarms, Because my lover calls me spouse, And takes me to her arms. This night no sound of breakers be— Unless my Alice be the sea.

Of man and maid in all the world Is stilled the swift caress, Because my lover has me curled In her own loveliness No kiss be such a night as this— Unless my Alice be the kiss.

This night—O never dawn shall crest The world of wakening, Because my lover has my breast On hers for dawn and spring. This night shall never be withdrawn— Unless my Alice be the dawn. A Novel Preface.

This is extracted from “Ambergris, a selection of poems of Aleister Crowley” (Elkin Mathews)—the most interesting volume of English verse seen this year. Crowley was met years ago in “The English Critical Review,” and has occurred here and there since, seeming always extraordinary. He is extraordinary—in his work, in the fine portrait affixed to his work, and in his preface. "In response to a widely spread lack of interest in my writings I have consented to publish a small and unrepresentative selection of the same. With characteristic cunning I have not included any poems published later than the third volume of my collected works. The selection has been made by a committee of seven competent persons, sitting separately. Only those poems have been included which obtained a majority vote. This volume, thus almost ostentatiously democratic, is therefore now submitted to the British public with the fullest confidence that it will be received with exactly the same amount of acclamation as that to which I have become accustomed."

"A Book of Verse."

The little volume of 200 pages, at 3/6, is commended as a pleasure to every amateur of poetry in Australia. If you would have more, the author flaunts his opulence in two pages of final advertisement, where twenty-eight published items are offered in Japanese vellum wrappers, and in green camel's hair wrappers and in blue wrappers and orange wrappers, at £2 2/ each or less—a poetical bargain counter. Rosa Inferni, for instance, in 8pp. royal 4to and an orange wrapper costs only 16/—or 2/ per page—although a lithograph from a water-color by Rodin is added. Crowley is a devotee of Rodin, and deserves to be. One does not remember any verse so plastic as some in the earlier pages of Ambergris. Crowley writes shapes, beautiful shapes, beautiful colored shapes like chryselephantine statuettes. All readers of verse know that there is ear-poetry and eye-poetry that sounds well and looks ill, and poetry that looks well and sounds ill. Crowley makes an unusual appeal both to eye and to ear. His ivory shapes go singing themselves golden tunes. In particular he has a gift of good beginnings, he attacks admirably:—

Rain, rain, in May. The river sadly flows . . .

Sing, happy nightingale, sing; Past is the season of weeping . . .

In middle music of Apollo's corn She stood, the reaper, challenging a kiss . . .

She fades as starlight on the stream, As dewfall in the dell . . .

More Than Craft.

If form were all; Crowley fails in emotion: his verse does not yield that ecstasy that adds the last drop to the brimming vase; he is always evident, never ineffable. Nor although original, is he highly, compellingly original; he does not lead us to unfooted fields of dream; at most he finds a new path in the familiar territory. Yet to call him "minor" is to do him injustice; he has the voice, though not the great imagination; and his skill with lines and rhymes, words and phrases, is more than craft. He is not "minor" because he has a pulse and a strong pinion; he does not flutter, he soars. Soars best when closest earth: his abstractions are empty; he needs the living model to warm his art. Then with a puff from swollen Eros:—

One kiss, like snow, to sip, Cool fragrance from thy lip To melt on mine; One kiss, a white-sail ship To laugh and leap and dip Her brows divine; One kiss, a sunbeam faint With love of a sweet saint, Stolen with a sacrament In the night’s shrine!

One kiss, like moonlight cold Lighting with floral gold The lake’s low tune; One kiss, one flower to fold, On its own calyx rolled At night, in June! One kiss, like dewfall, drawn A veil o’er leaf and lawn— Mix night, and morn, and dawn, Dew, flower, and moon! Crowley has travelled, and writes harmonious stanzas for Hawaii, for Egypt, even for Hong Kong. Perhaps after Verhaeren (for we catch an echo here and there) he cries:—

To sea! Before us leap the waves; The wild white combers follow. Invoke, ye melancholy slaves, The morning of Apollo! . . .

The ship is trim; to sea! to sea! Take life in either hand, Crush out its wine for you and me. And drink, and understand!

Or.

The spears of the night at her onset Are lords of the day for a while, The magical green of the sunset, The magical blue of the Nile. Afloat are the gales In our slumberous sails On the beautiful breast of the Nile.

Exulting Vitality.

A little precious, Crowley must not be deemed to pose, despite his preface: often it is the excess of exulting vitality that is called a pose by timid little people. Admit, though, that this excess here and there arouses the comic spirit, as when the poet reviles his Muse in face of his Lady:—

Ye unavailaing eagle-flights of song! Of wife! these do thee wrong.

Thou knowest how I was blind; How for mere minutes they pure presence Was nought; was ill defined; A smudge across my mind, Drivelling in its brutal essence, Hog-wallowing in poetry, Incapable of thee.

Yet, a few lines below:

O thou! didst thou regret? Wast thou asleep as I? Didst thou not love me yet For, know! The moon is not the moon until She hath the knowledge to fulfil Her music, till she know herself the moon.

There are many Shakespearian touches in Crowley, and not so many Shakespearian lapses. If you stress the lapses, he gives a line for maltreating—

Smite! but I must sing on. . .

What a motto for Australian bards, Ifray! Accept Crowley or refuse him, he brings his own atmosphere, and captivates you, and finally captures: there is such a tide of life in him, though it does not rise through the finest poetic brain (nor did Shakespeare’s tide). And for closing, let the Star-Goddess sing a stanza of Orpheus dead—and risen.

For brighter from age unto age The weary old world shall renew Its life at the lips of the sage, Its love at the lips of the dew. With kisses and tears The return of the years Is sure as the starlight is true.

There is one that hath sought me and found me In the heart of the sand and the snow: He hath caught me, and held me, and bound me, In the lands where no flower may grow, His voice is a spell. Hath enchanted me well! I am his, did I will it or no. . . —Daily Herald, 10 December 1910. |

|||||||||||||||||||||