100th

MP

|

THE

100th

MONKEY

PRESS |

|

|

|

Limited Editions by Aleister Crowley & Victor B. Neuburg |

|

Bibliographies |

|

Download Texts

»

Aleister

Crowley

WANTED !!NEW!!

|

|

CLOUDS WITHOUT WATER |

|

Image Thumbnails |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Title: |

Clouds Without Water. Edited from a Private MS. by Rev. C. Verey. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Variations: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Publisher: |

Privately published.6 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Printer: |

Philippe Renouard, Paris.6 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Published At: |

London.1 Although the title page states London, this book was actually printed in Paris.6 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Date: |

1909.1 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Edition: |

First edition. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pages: |

ii + xxii + 143.2 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Price: |

5 shillings.5 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Remarks: |

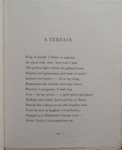

Published under the pseudonym of the Reverend C. Verey.1 The first letters in each line of A Terzain from this book spell out the name of artist Kathleen Bruce who once sculpted Crowley as an "Enchanted Prince."7 A copy went to Karl Germer with an inscription by Crowley which read “To Karl Germer in token of good will Aleister Crowley. June 22, 1925 e.v.”4 Crowley requested that a copy be sent to Aldous Huxley.8 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pagination:2 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contents: |

- Preface - The Manuscript - A Terzain - The Auger - The Alchemist - The Hermit - The Thaumaturge - The Black Mass - The Adept - The Vampire - The Initiation |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Author’s Working Versions: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other Known Editions: |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bibliographic Sources: |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Comments by Aleister Crowley: |

I was much touched by Henley’s kindness in inviting me. I have never lost the childlike humility which characterized all truly great men. Modesty is its parody. I had to wait some little while before he came down. When he did so, he was obviously suffering severe physical distress. Like Marcel Schwob himself, he was a martyr to constipation. He told me that the first half of every day was a long and painful struggle to overcome the devastating agony of his body. Only three weeks later he died. He was engaged in various tremendous literary tasks and yet he could give up a day to welcome a young and unknown writer! I could not pretend to myself that so great a man could feel any real interest in me. It never occurred to me that he might have read anything of mine and thought it promising. I took, and take, his action for sheer human kindness. I probably behaved with my usual gaucherie. The presence of anyone whom I really respect always awakes my congenital shyness, always overawes me. Henley’s famous poem (which Frank Harris regards as “the bombast of Antient Pistol”) appealed intensely to my deepest feeling about man’s place in the universe; that he is a Titan overwhelmed by the gods but not surrendering. And the form or the poem is superb. It is in line with all the great English expressions of the essential English spirit, a certain blindness, brutality and arrogance, no doubt, as in “Rule Britannia”, “Boadicea”, “The Garb of Old Gaul”, “The British Grenadiers”, “Hearts of Oak”, “Toll for the Brave”, “Ye Mariners of England”, et hoc genus omne; but with all that, indomitable courage to be, to do and to suffer as fate may demand. I never thought much of the rest of Henley’s verse, distinguished as it is for vigour and depth of observation. It simply does not come within my definition of poetry, which is this: A poem is a series of words so arranged that the combination of meaning, rhythm and rime produces the definitely magical effect of exalting the soul to divine ecstasy. Edgar Allan Poe and Arthur Machen share this view. Henley’s poem conforms with this criterion. I told him what I was doing about Rodin. His view was that the sonnet had been worked out and he advised me to try the Shakespearian sonnet or quatorzain. I immediately attempted the form in the train that evening and produced the quatorzain on himself from which I have quoted above. I recognized at once that the quatorzain was in fact much better suited to my rugged sincerity than the suavity of the Italian form, so I composed a number of poems in the new mode. In fact, I fell in love with it. I invented improvements by the introduction of anapaests wherever the storm of the metre might be maddened to typhoon by so doing, and it may be that history will yet say that Clouds without Water, a story told in quatorzains, as Alice in sonnets, is my supreme lyrical masterpiece. At least I have not died without the joy of knowing that no less a lover of literature than the world-famous Shakespearian Lecturer, Dr. Louis Umfraville Wilkinson, has dared to confess publicly that Clouds without Water is “the most tremendous and the most real love poem since Shakespeare’s sonnets” in the famous essay “A Plea for Better Morals”. But I anticipate. Clouds without Water came four years later. I am still sitting sleepily in the twilight in Europe; after my day’s labour three years long in the blazing sun of the great world. — The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. New York, NY. Hill and Wang, 1969. Pages 344-346 ______________________________

In October of this year* I began Clouds without Water, fully described elsewhere.

* 1907 ______________________________

This year was indeed my annus mirabilis in poetry. It began with Clouds Without Water, to which I have already called attention in the matter of its technique. The question of its inspiration is not less interesting. At Coulsdon, at the very moment when my conjugal cloudburst was impending, I had met one of the most exquisitely beautiful young girls, by English standards, that ever breathed and blushed. She did not appeal to me only as a man; she was the very incarnation of my dreams as a poet. Her name was Vera; but she called herself “Lola”. To her I dedicated Gargoyles with a little prose poem, and the quatrain (in the spirit of Catullus) “Kneel down, dear maiden o’mine.” It was after her that my wife called the new baby! Lola was the inspiration of the first four sections of Clouds Without Water. Somehow I lost sight of her, and in the fifth section she gets mixed up with another girl who inspired entirely sections six and seven. But the poem was still incomplete. I wanted a dramatic climax, and for this I had to go to get a third model. Number two was an old friend. I had known her in Paris in 1902. She was one of the intimates of my fiancée. She was studying sculpture under Rodin and was unquestionably his best woman pupil. — The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. New York, NY. Hill and Wang, 1969. Pages 555-556 ______________________________

But back to my sculptress! To her I dedicated Rodin in Rime and Clouds Without Water itself—not openly; our love affair being no business of other people, and in any case being too much ginger for the “hoi” “polloi”, but in such ways as would have recommended themselves to Edgar Allan Poe. — The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. New York, NY. Hill and Wang, 1969. Page 557 ______________________________

Now as to section eight of Clouds Without Water, “The Initiation”, I hardly know why I should have felt it necessary to conclude on such an appalling chord. The powers of life and death combine in their most frightful forms to compel the lovers to seek refuge in suicide, which they, however, regard as victory. “The poison takes us: Chi alpha iota rho epsilon tau epsilon nu iota chi omega mu epsilon nu .” The answer is that the happy ending would have been banal. The tragedy of Eros is that he is dogged by Anteros. It is the most terrible of all anticlimaxes to have to return to the petty life which is bound by space and time. I had the option of coming down to earth or enlisting death in my service. I chose the latter course. My model was a woman very distinguished and very well known in London society. She had already figured as the heroine of Felix. She had been one of the best and most loyal friends of Oscar Wilde. She was herself a writer of subtlety and distinction, but she filled me with fascination and horror. She gave me the idea of a devourer of human corpses, being herself already dead. Fierce and grotesque passion sprang up for the few days necessary to give me the required inspiration for my climax. I could only heighten the intoxication of love by spurring it to insanity. — The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. New York, NY. Hill and Wang, 1969. Pages 557-558 ______________________________

I went back to Paris on July 8th.* I worked on Clouds Without Water, Sir Palamedes, The World’s Tragedy and “Mr. Todd”. * 1908 — The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. New York, NY. Hill and Wang, 1969. Page 573 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Reviews: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||