100th

MP

|

THE

100th

MONKEY

PRESS |

|

|

|

Limited Editions by Aleister Crowley & Victor B. Neuburg |

|

Bibliographies |

|

Download Texts

»

Aleister

Crowley

WANTED !!NEW!!

|

|

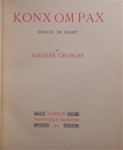

KONX OM PAX |

|

Image Thumbnails |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Title: |

Konx Om Pax. Essays in Light. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Variations: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Publisher: |

Privately published.1 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Printer: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Published At: |

London.1 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Date: |

circa November 1907. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Edition: |

First Edition, First Issue. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pages: |

xix + 108 + 2 page catalog of Crowley's works + 10 pages of reviews for J.F.C. Fuller’s The Star in the West.5 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Price: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Remarks: |

Martin Starr states7 this issue of Konx Om Pax has the portrait of Aleister Crowley, by Aimé Dupont, tipped in as a frontispiece, but the one instance that I have actually seen did not have such.5 The 10 page compilation of reviews of Fuller’s The Star in the West contains three additional reviews than what is contained in both the second and third issues and omits the imprint of the Chiswick Press.7 See photos to the right. The front cover is said to have been designed by Crowley while on hashish7 on 2 October 1907.10 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pagination:2 |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contents: |

- Dedication and Counter-Dedication - The Wake World - Ali Sloper - Thien Tao - The Stone of Abiegnus |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Author’s Working Versions: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other Known Editions: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bibliographic Sources: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Comments by Aleister Crowley: |

The “Dedication and Counter-Dedication” of Konx Om Pax is wholly admirable and it rises to a delightful satirical climax of four stanzas on the “empty-headed Athenians”. “The Wake World” is a sublime description of the Path of the Wise, rendered picturesque by the use of the symbols of the Taro, and charming by its personification of the soul as a maiden. “My name is Lola, because I am the Key of Delights, and the other children in my dream call me Lola Daydream.” “Ali Sloper; or the Forty Liars” shows traces of my old vulgarity. The dramatis personae contain a lot of bad puns and personal gibes, but the dialogue shows decided improvement; and the “Essay on Truth” is both acute and witty, with few blemishes. “Thien Tao” gives my solution of the main ethical and philosophical problems of humanity with a description of the general method of emancipating oneself from the obsession of one’s own ideas, while there are passages of remarkable eloquence. The last essay in Konx Om Pax, “The Stone of the Philosophers which is hidden in Abiegnus, the Rosicrucian Mountain of Initiation”, is really beyond praise. Its genesis is interesting. I had written at odd times, but mostly during my travels with the Earl of Tankerville, a number of odd lyrics. The idea came to me that I might enhance their value by setting them in prose. I therefore wrote a symposium of a poet, a traveller, a philosophical globetrotter, an adept, a classical scholar and a doctor. They are made to converse about the chronic calamity of society, and the poems (ostensibly written by one or other of the men) carry on the thought. The result is, in reality, a new form of art; and I certainly assisted the lyrics by giving them appropriate springboards. — The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. New York, NY. Hill and Wang, 1969. Page 537. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Reviews: |

If the reader wishes to be shocked, he might do worse than read Konx om Pax, or Essays in Light, by Aleister Crowley. But let him not turn upon the Occult reviewer afterwards for what he reads therein. The title of the volume, if we may believe the author of The Lords of the Ghostland, means "Go in Peace," and was the word of dismissal used to the participants after the ceremony of the Eleusinian mysteries was completed. But the only word we are able to recognize is the Latin "Pax," which seems somewhat inappropriate in a Greek ceremonial. The book consists of a series of skits, blasphemous, profane, profound and humorous. Sometimes it is occultism that is parodied; sometimes it is the politician who is caricatured; sometimes it is the follies and foibles of the human race generally that are held up to ridicule. Take this for instance, on politics:—

As yet however, the country was not irretrievably doomed. A system of intrigue and blackmail, elaborated by the governing classes to the highest degree of efficiency, acted as a powerful counterpoise. In theory all were equal; in practice the permanent officials, the real rulers of the country, were a distinguished and trustworthy body of men. Their interest was to govern well, for any civil or foreign disturbance would undoubtedly have fanned the sparks of discontent into the roaring flame of revolution. And discontent there was. The unsuccessful cheesemongers were very bitter against the Upper House; and those who failed in examinations wrote appalling diatribes against the folly of the educational system. The trouble was that they were right: the government was well enough in fact, but in theory had hardly a leg to stand on. In view of the growing clamour, the official classes were perturbed; for many of their number were intelligent enough to see that a thoroughly irrational system, however well it may work in practice, cannot for ever be maintained against the attacks of those who, though they may be secretly stigmatized as doctrinaires, can bring forward unanswerable arguments. The people had power, but not reason; so were amenable to the fallacies which they mistook for reason and not to the power which they would have imagined to be tyranny. An intelligent plebs is docile; an educated canaille expects everything to be logical. The shallow sophisms of the Socialist were intelligible propositions of the Tory.

The verses, of which there are a good many, are very forcible and realistic. A fair sample of the author's style is this, quoted from the "Stone of the Philosophers":—

You would not dally with Doreen, Because her fairness was to fade, Because you know the things unclean That go to make a mortal maid.

I, if her rotten corpse were mine, Would take it as my natural food, Denying all but the Divine, Alike in evil and in good.

The book shows genius, but a genius that might have been better directed; many passages are quite unquotable. If Mr. Crowley would content himself with calling a spade a space it would be well. The volume is bound in a black and white cover that one cannot look at without blinking. —The Occult Review, July 1908. ______________________________

The Light wherein he writes is the L.V.X., of that which, first mastering and then transcending the reason, illumines all the darkness caused by the interference of the opposite waves of thought. . . . It is one of the most suggestive definitions of KONX—the LVX of the Brethren of the Rosy Cross—that it transcends all the possible pairs of opposites. Nor does this sound nonsensical to those who are acquainted with that LVX. But to those who do not it must remain as obscure and ridiculous as spherical trigonometry to the inhabitants of Flatland. —The Times, date unknown. ______________________________

The author is evidently that rare combination of genius, a humorist and a philosopher. For pages he will bewilder the mind with abstruse esoteric pronouncements, and then, all of a sudden, he will reduce his readers to hysterics with some surprisingly quaint conceit. I was unlucky to begin reading him at breakfast and I was moved to so much laughter that I watered my bread with my tears and barely escaped a convulsion. —John Bull, Herbert Viviam, date unknown. ______________________________

BOOK OF THE WEEK The Beautiful What.* (*Konx om Pax. By Aleister Crowley. Publishing Co. Priceless.)

The flamboyant flame of the sun, ardent with aeonpent energy, revolted, turned aside from his immemorial mistress, wandered across the track of the Seven Dials that perpetually revolve amid the cloudless essence of Q.F.D.N.W. Rejoicing on his way he fell in with the refulgent ray of the moon rising with hyaline glint from an epileptiform seizure in the Tychonic Crater. Behold the fierce flame has nurled the rorty ray; they have united in the gusty anguish of love. Their passionate embraces reverberate to distant Neptune, transfusing the Dusky Ring of Saturn with a mad violence that would shame the gobbler’s gill, who broke from her darling planet and taking the outer rings in her wake fell to erratic vibrations, disturbing enough to weary Astronomer-Royals. Be glad, O ye earth ; rejoice exceedingly, my tender Pleiades; frolic, leap-frog, 0 bright-eyed Arcturus; and you Orion (7= matter vanquished by Spirit), skip, dance adown the Milky-Way. The Moon’s Ray is in travail ; her groans re-echo on the earth, the seas roar, the mountains spin, the cities are swallowed like Whitstable Natives. He is born. The cymbals clash, the oboes peal, the trumpets sound shrill and clear. The Star in the West is born. Aleister Crowley = 50 = 5 = A Magician. Born to misfortune, Trouble, Strife, Fierce burning Anger, Deathless Struggle must be your lot. Lo, is it not so written in the Kabbalah? Yours also is the Reincarnation and the Life, O laughing lion that is to be! Here you have distilled for our delight the inner spirit of the Tulip’s form, the sweet secret mystery of the Rose’s perfume; you have set them free from all that is material whilst preserving all that is sensual. "So also the old mystics were right who saw in every phenomenon a dog-faced demon apt only to seduce the soul from the sacred mystery.” Yes, but the phenomenon shall it not be as another sacred mystery; the force of attraction still to be interpreted in terms of God and the Psyche? We shall reward you by befoulment, by cant, by misunderstanding, and by understanding. This to you who wear the Phrygian cap, not as symbol of Liberty, O ribald ones, but of sacrifice and victory, of Inmost Enlightenment, of the soul’s deliverance from the fetters of the very soul itself — fear not: you are not “replacing truth of thought by mere expertness of mechanical skill.” You who hold more skill and more power than your great English predecessor, Robertus de Fluctibus, you have not feared to reveal “the Arcana which are in the Adytum of God-nourished Silence” to those who, abandoning nothing, will sail in the company of the Brethren of the Rosy Cross towards the Limbus, that outer, unknown world encircling so many a universe. Who would have the invitation general (although it is also not for the elect in any ordinary sense)? These you need scarce repel.

In fine, I have precious little use For empty-headed Athenians The birds I have snared shall all go loose, They are empty-headed Athenians. I thought perhaps I might do some good, But it’s ten to one if I ever should — And I doubt if I would save, if I could, Such empty-headed Athenians.

Since this is a Socialist review, I must be at pains to notice “Thien Tao," a political essay. Expressed symbolically the main criticism we have to offer is —

r — t =0 where — = 0.

With this the empty-headed Athenians will remain unsatisfied, and we should be deprived of the epiphenomenal auxiliaries which sustain us in our search for the master-key which is to unlock the portals of all mystery; this mystery, ever elusive yet syntonic, in its appeal to us. Here then let me quote: “The recent extension of the franchise to women had rendered the Yoshiwara the most formidable of the political organizations, while the physique of the nation had been seriously impaired by the results of a law which, by assuring them in case of injury or illness of a fife-long competence in idleness which they could never have obtained otherwise by the most laborious toil, encouraged all workers to be utterly careless of their health.” The disciples of the Rosy Cross held that woman was an accident, an obtrusion upon the ramparts of the world’s plan. Virgo-Scipio is a two-fold sign. Si igitur sub serpentis imagine Phallium Signum intelligimus, quam plana sunt et concinna cuncta pictura lineamenta." This conception of the universe as a male one is tenable whole and wholesome, although there was ever a place for woman as virgin freed from the material gross greedy things ere she partook of “the fruit of that forbidden Tree, whose mortal taste, Brought death into the world, and all our woe.” To Mr. Crowley this view, like the Occidental conception towards which we are now thrusting out tentacles of the roles of man and woman furnishes nothing but matter for a jest. Now these views are mutually exclusive, but are equally tenable. What is wearisome stale and unprofitable is just our present-day molluscan attitude. We sit quivering in the dry sand, awaiting the seas that shall never reach us, but which we should go forth to meet, yet afraid to clamber back up the high cliffs. Mr. Crowley does not display his usual courage here, nor that independence of judgment which nearly everywhere, even when he is most wrong, commends our loving admiration. Mr. Crowley should arrive at his own conclusions regarding the question. As to whether his views are shared by the many or the few is equally impertinent. Does Mr. Crowley seriously regard laborious toil as ever conducive to health? Toil, laborious or not, is all work undertaken without the spirit of joy, ease, irresponsibility, and is the root of all evil; it can never lead to any form of well-being. “The government was well enough in fact, but in theory had hardly a leg to stand upon.” This is not obscurity, but nonsense of the most painful and blatant character. Facts and theories do not suggest contradictory opposition. Facts are but the tortured expressions of stupid people who cannot learn to think. Mr. Crowley becomes the friend and follower of Herbert Spencer, Lord Avebury, Arnold-Forster, and all the rest of parish-council shop-keeping philosophers who conceive that Socialism aims at the equalisation of the individual by furnishing a like environment and like education for all. Or does he satirise our own day by his remark that “The theory of heredity had broken down, and the ennoblement of the cheesemongers made it not only false, but ridiculous”? How can a theory of heredity ever break down? There is some excuse for Mr. Crowley in the writings of many Socialists, but the philosopher is not guided by the fallacies of others; he dives below and discovers the pearls for himself. Myself and one or two others can undeceive Mr. Crowley, but he can do it much better himself. He knows that there is no freedom whilst the soul is chained; my Socialism will remove the fetters. Another complaint, and my last. Kwaw devotes some years to the pursuit of philosophy. “In the first year he disciplined and conquered his body and his emotions. In the next six years he disciplined and conquered his mind and its thoughts.” For Mr. Crowley I must recommend that he re-study the sixty-fourth chapter of the Book of the Dead, not in the English translation, however. For our readers, I recommend a study of Mr. Crowley’s The Wake World and The Stone of the Philosophers, the first especially containing all the beauty, the sense of haunting mystery, with an entirely divine prescience that surely distinguishes Mr. Crowley from the common flock of writers. By the way, I should mention that the prose is interspersed with some verse; his rhymes, for instance, “The Suspicious Earl" — are as startling and Frolicsome as any you will find in Hudibras, his rhythm is varied, whilst he has a sense of music in words from which even the Irish renascents may learn. It is Mr. Crowley’s pleasure, after soaring in the heights, to suddenly fling himself upon the earth in search of carrion, much as I have watched the condor circling in the Andean ether plump ghoul-like through the air as it sniffed some bespattered carcase. However, in a vestryman age we cannot deny even Mr. Crowley his little joke. —The New Age, Dr. M. D. Eder, 29 February, 1908. ______________________________

He is a lofty idealist. He sings like a lark at the gates of heaven. “Konx Om Pax” is the apotheosis of extravagance. the last word in eccentricity. A prettily told fairy-story “for babes and sucklings” has “explanatory notes in Hebrew and Latin for the wise and prudent”—which notes, as far as we can see, explain nothing—together with a weird preface in scraps of twelve or fifteen languages. The best poetry in the book is contained in the last section—“The Stone of the Philosophers.” Here is some fine work. —The Literary Guide, date unknown. ______________________________

Verbal fireworks. A wild and wasteful heterogeneous collection of weird words. . . Still, one cannot but admire the author’s oftimes skilful jugglery with words and his kaleidoscopically changing humour, even though one deplores his prodigality. —The Literary Guide, date unknown. ______________________________

This disconcerting volume of nebulous disquisitions in

amorphous prose, relieved at intervals by verses which are

formally musical, but substantially inconsequential and inane. .

. . A rambling miscellany which along with much quizzing and

much nonsense, vaguely reflects some of the ideas of the day. .

. . More tolerable in its verse than in its prose, for a poet is

not expected to be sensible. Readers who are already acquainted

with the writings of Mr. Aleister Crowley need not be told that

his imagination disports itself in a manner calculated to stun

the middle classes. ______________________________

What can one really say about a production such as this? At best it looks like one big sneer at the Christian faith. There is a great deal that is undoubtedly smart and clever, revealing at times real genius, but presented in such a chaotic mystic rigmarole that the reader must needs stop his ears. . . . There is some marvellous verse, but there is more in it to deplore than to admire. We cannot conceive how a man with the culture of Mr. Crowley could sit down and write and see put into print some of the stanzas. This is essentially a top shelf book, not suitable for all. —The Perthshire Courier, date unknown. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||