100th

MP

|

THE

100th

MONKEY

PRESS |

|

|

|

Limited Editions by Aleister Crowley & Victor B. Neuburg |

|

Bibliographies |

|

Download Texts

»

Aleister

Crowley

WANTED !!NEW!!

|

|

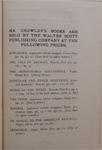

THE STAR IN THE WEST (POPULAR EDITION) |

|

Image Thumbnails |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Title: |

The Star in the West. A Critical Essay on the Works of Aleister Crowley. (Popular Edition) |

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Variations: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Publisher: |

Bakunin Press.1 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Printer: |

Chiswick Press: Charles Whittingham and Co., Tooks Court, Chancery Lane, London.2 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Published At: |

London.1 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Date: |

1908.1 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Edition: |

Third edition.1 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pages: |

x + 328 + iv (publisher's catalog).2 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Price: |

One shilling and six pence.2 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Remarks: |

This is the "Popular" edition.2 This edition has an introduction addressed to "friends of freedom" by Guy A. Aldred.2 J. F. C. Fuller originally wrote this as an entry in a competition Crowley held for the best essay on his own literary work. Fuller rewrote the essay with Crowley's assistance and it was published.3 |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pagination:2

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contents: |

- Preface. - Foreword. - I. The Looking Glass. - II. The Virgin. - III. The Harlot. - IV. The Mother - V. The Old Bottle. - VI. The Cup. - VII. The New Wine. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Author’s Working Versions: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Other Known Editions: |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Bibliographic Sources: |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Comments by Aleister Crowley: |

The style of The Star in the West is trenchant and picturesque. Its only fault is a tendency to overloading. I could have wished a more critical and less adoring study of my work; but his enthusiasm was genuine, and guaranteed our personal relations in such sort that my friendship wit him is one of the dearest memories of my life. I dedicated The Winged Beetle to him. — The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. New York, NY. Hill and Wang, 1969. Page 544. ______________________________

The Star in the West was published in 1907 and was widely reviewed; for the most part, favourably. In particular, Soror S. S. D. D. (Mrs. Emery or "Florence Far" as she was variously known) wrote a very full criticism of it in the New Age. Some of it is so prophetic that it must be quoted here:

It is a hydra-headed monster, this London Opinion, but we should not be at all surprised to see an almost unparalleled event, namely, everyone of those hydra-heads moving with a single purpose, and that the denunciation of Mr. Aleister Crowley and all his works. Now this would be a remarkable achievement for a young gentleman who only left Cambridge quite a few years ago. It requires a certain amount of serious purpose to stir Public Opinion into active opposition, and the only question is, has Mr. Crowley a serious purpose? ... Such are some of the sensations described by Aleister Crowley in his quest for the discovery of his Relation with the Absolute. His power of expression is extraordinary; his kite flies, but he never fails to jerk it back to earth with some touch of ridicule or pathos which makes it still an open question whether he will excite that life-giving animosity on the part of Public Opinion which, as we have hinted, is only accorded to the most dangerous thinkers.

I was enormously encouraged by this article. I knew how serious my purpose was. She had reassured me on the point where my faith wavered. I had become so accustomed to columns of eloquent praise from the most important people in the world of letters, which had not sold a dozen copies; to long controversial criticism from such men as G. K. Chesterton, which had fallen absolutely flat. People acquiesced in me as the only living poet of any magnitude. (There were many better known and more highly reputed poets---Francis Thompson, W. B. Yeats, Rudyard Kipling, and later John Masefield, Rupert Brooke and other small fry, whose achievement at the best was limited by the narrowness of their ambitions. I at least was aiming at the highest.) — The Confessions of Aleister Crowley. New York, NY. Hill and Wang, 1969. Pages 544-545. |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Reviews: |

What is this wonderful abstraction we call the British public? Before Mafeking night we knew quite well what it was. The female part of it was Mrs. Grundy, the well-known old lady in white cotton stockings, elastic-side boots, stuffy petticoats, and a grim determination to give everyone a bit of her mind. The male part of it was an idealistic old gentleman of prolific habits with a pathetic faith in the British constitution and a habit of locking up the house at ten o’clock every weekday and at half-past nine on Sunday. This British Androgyne has vanished, and we are ruled instead by a protean monster whom we worship under the name of Public Opinion. Every class has its own opinion, for are we not a free country? London has its “Liza of Lambeth” set, its Marie Corelli set, its Arthur Wing Pinero set, its George Bernard Shaw set, its Sir William Crooks set, its Royal smart set, its Lord Kelvin set, its individual pleasure seekers, its perverts, its literary, artistic, religious, and philosophical specialists. It is a hydra-headed-monster, this London Opinion, but we should not be at all surprised to see an almost unparalleled event, namely, everyone of those hydra-heads moving with a single purpose and that the denunciation of Mr. Aleister Crowley and all his works. No this would be a remarkable achievement for a young gentleman who only left Cambridge quite a few years ago. It requires a certain amount of serious purpose to stir Public Opinion into active opposition, and the only question is, has Mr. Crowley a serious purpose? Our first instinctive feeling is that “It is damned clever, but it won’t do.” That is succeeded by the certainty that “It is raving madness”; and a final judgment that the young man is a remarkable product of an unremarkable age. The writing is not sane; but we have long ago outworn the illusion that sanity is a symptom of cleverness. Still, the writer has the serious fault common to Browning and Shaw: he is incapable of a clear straightforward statement. We all have met the old lady who, in trying to recount some personal adventures, wanders off into the biographies of everyone mentioned, and eventually forgets to tell us the point of her story. We suffer from this in Mr. Shaw’s plays and in Browning’s “Sordello.” Are we willing to suffer from it in order to discover the secret of Mr. Crowley’s mind? Is the game worth the candle? The time of being August and the weather inclement, we are inclined to think it possibly may be. Now is the appointed season, so let us hasten to study the world of Mr. Crowley before the rush of our own lives reabsorbs us. Our principal objection to Mr. Crowley’s style is that it is redundant. For instance, the organs of generation are always cropping up in unexpected places, such as in Mr. Crowley’s brain—which is said to be pregnant—and in Rosa Mundi’s heart—which contains a symbol sadly out of lace anatomically. All this reminds us of the ways of little boys; but surely Mr. Crowley might suppress these symptoms of the extreme youth of the virile spirit, and discipline his imagination with a study of the separate functions of the separate organs of the body. We are quite aware that the old fallacy that sex is the source of all the passion of the human race supports Mr. Crowley and his laudatory critic Captain Fuller in their tendency to use sexual imagery in excess; but surely the fallacy has been exploded. We have all read Weininger, who demonstrates that a large proportion of the human race have no special characteristics; that the absolutely female woman or virile man can hardly be said to exist at all; but that the border line between the physiological symptoms of sex is becoming less marked in each generation. There is a force of dominance universally manifest, but that force is exercised by every living creature; it impenetrates the kingdoms of the sea and land and air; and sex is only a small part of its purpose. However, Mr. Crowley has chosen to focus his attention on sex, and Captain Fuller has dutifully followed him in 144 pages. On the whole, we think Mr. Crowley may be congratulated. He manages to describe the utmost excess of desire when a rejected lover possesses and finally devours the dead body of his beloved, in terms which do not shock us in English any more than such descriptions usually shock us in French. This is a very exceptional accomplishment, as anyone may realise who has read French novels in English. Here is one of Mr. Crowley’s typical climaxes:—

The host is lifted up. Behold The vintage spilt, the broken bread! I feast upon the cruel cold Pale body that was ripe and red. Only her head, her palms, her feet, I kissed all night, and did not eat.

“But had it not been for the garter, I might never have seen the star,” Mr. Crowley says. Hence we look from the garter to the more starry part of Mr. Crowley’s work, for he has learned a good deal about Eastern philosophy at first hand, which is well worth consideration. Captain Fuller describes “Crowleyanity” as being “the conscious communion with God on the part of an Atheist, a transcending of reason by skepticism of the instrument, and the limitation of skepticism by direct consciousness of the Absolute.” He defines God later on as the Relation between man and the Absolute, and he says “it is the search after this relationship—God—that Crowley so frequently and ardently depicts.” He cries in one place:—

“By the sun’s heat, that brooks not his eclipse And dissipates the welcome clouds of rain. God! have Thou pity soon on this amazing pain.”

And in another describes the mystic goal—

“So shalt thou conquer space, and lastly climb The walls of Time, And by the golden path the great have trod Reach up to God.”

He grapples with the problems of human consciousness and he has realized the absoluteness of zero. He perceives that when consciousness, as we know it, is absolutely indrawn, so that is exists in pure isolation, it knows an ecstasy which can only be expressed in the thought, “I do not exist.” This last paradox of human manifestation has been perceived by every school of mystics. “Man’s darkness is a leathern sheath, Myself the sun-bright sword,” is the feeling of the consciousness as it returns to its human state, admirably expressed by Mr. Crowley in “Mysteries” (vol. i., p. 105). Finally he is driven to the utterance of one who has gained final liberation from human illusion:—

So lifts the agony of the world From this my head that bowed awhile Before the terror suddenly shown. The nameless fear for self, far hurled By death to dissolution vile, Fades as the royal truth is known: Though change and sorrow range and roll, There is no self—there is no soul.

The essay on Science and Buddhism (p. 244 vol. ii. of The Collected Works) is valuable, proving as it does that Buddhistic philosophy is a logical development from observed facts. Captain Fuller declares that the Agnostic principles of “Crowleyanity” may be summed up as follows:—

“Believe nothing till you find it out for yourself.” “Say not ‘I have a soul’ before you feel that you have a soul.” “Say not ‘There is a God’ before you experience that there is a God.” “You can never understand till you have experienced.” “You can never experience till you get beyond reason.”

In a word, his command to his followers is, Know or Doubt; do not believe. We are, he says, “surrounded with an appearance of Truth,” and Reason is our guide. To become part of Wisdom we must leave Reason on one side. No doubt men differ in qualities, but these differences and progressive states have nothing to do with the sudden awakening of the faculty which lies beyond reason—that faculty of seeing clearly through the magical appearances surrounding us and perceiving the cause beyond the falsity of its effects. Mr. Crowley says, apropos of this, “It is no doubt more difficult to learn ‘Paradise Lost’ by heart than ‘We are Seven’; but when you have done it you are no better at figure skating.” He quotes as the great guiding scripture of his life a Buddhist Sutta (ii. 33):—“Therefore, O Ananda, be ye lamps unto yourselves. Be ye a refuge to yourselves. Betake yourself to no external refuge.” How is this inward mystery revealed? The answer is in the East by Yoga, and in the West by Magic; in the East by an entirely artificial and scientific method, in the West by a stimulation and sudden outflowing of the poetic faculty. The East, we may take it, is almost entirely static, whilst the West is wholely dynamic:—

Life flees Down corridors of centuries Pillar by pillar, and is lost. Life after life in wild appeal Cries to the master; he remains And thinks not.

● ● ● ●

Bright Sun of Knowledge, in me rise, Lead me to those exalted skies To live and love and understand! Paying no price, accepting nought—— The Giver and the Gift are one With the Receiver.”

Such are some of the sensations described by Aleister Crowley in his quest for the discovery of his Relation with the Absolute. His power of expression is extraordinary; his kite flies, but he never fails to jerk it back to earth with some touch of ridicule or bathos which makes it still an open question whether he will excite that life-giving animosity on the part of Public Opinion which, as we have hinted, is only accorded to the most dangerous thinkers. —The New Age, 29 August 1907 ______________________________

"The Star of the West," by Captain J. F. C. Fuller, is the title of a forthcoming critical essay upon the poetical and philosophical works of Aleister Crowley. In it a full account is given, not only of his iconoclasm towards many past and present systems of thought, but of his reconciliation of such apparent opposites as Theism and Atheism; Rationalism and Mysticism; Ethics, Buddhism, and the Qabalah. —The Hull Daily Mail, 26 June 1907 ______________________________

"The Star in the West," by Captain J. F. C. Fuller, is the title of a forthcoming critical essay upon the poetical and philosophical works of Aleister Crowley. In it a full account is given, not only of his iconoclasm towards many past and present systems of thought, but of his reconciliation of such apparent opposites as Theism and Atheism; Rationalism and Mysticism; Ethics, Buddhism, and the Qabalah; and all such earnest questions as The New Morality; The New Theology; The New Mysticism of the present day into one great Scientific Illuminism, which alone can guide us across this boisterous ocean of modern thought to a haven of perfect rest. The Walter Scott Publishing Co., Ltd., will issue Captain Fuller's work. —The Bath Chronicle, 4 July 1907 ______________________________

An extraordinary letter, enclosing a strange, elliptical card, has just been received at the Daily Mirror office. The substance of the letter, which is sent from a West End address, is as follows:— “Two days ago I received the enclosed card anonymously, and, just glancing at it briefly, thinking it an advertisement of some sort, I placed it on the mantelpiece. “Within a few minutes, disasters of a minor kind began to happen in my little home. “First, one of my most valuable vases fell to the ground and was smashed to pieces. My little clock stopped—the clock was near the card—and then I discovered to my amazement that my dear little canary lay dead at the bottom of its cage!

“I am fully convinced that the characters on the card have some evil influence. Please do not send the dreadful thing back to me.” Two London authorities on signs and hieroglyphics, Mr. Everard Green, F.S.A., and Mr. Sadler, librarian of the Freemason’s Hall, have been approached by the Daily Mirror, in the hope that they might be able to throw some light on the matter. Mr. Green said the arrangement of the signs was apparently meaningless. “It has nothing whatever to do with any heraldic signs,” he said, “It is probably the work of an individual, or of some small society.” Mr. Sadler on viewing the card remarked that it was totally erroneous to imagine that it had an evil influence. “There are Alpha and Omega—the beginning and the end—in the scales of justice, supported by the sword. Above all is the celestial crown, white the letterings are, as far as I can judge, mostly of a religious character. The lettering, ‘V.V.V.V.V.,’ however, I cannot understand. “I do not know to what society or order the card belongs.” It has nothing to do with Freemasonry. Perhaps some of our readers may be able to explain the origin of this mysterious card. —The Daily Mirror, 15 August 1907 ______________________________

Years ago, the saintly Novalis called Baruch de Spinoza “that God-intoxicated Man.” What would he have said had he lived to-day, and looked upon the face of Aleister Crowley, that glory revealed to us by the genius of Captain J. F. C. Fuller? Crowley has been reproached in some thoughtless or malicious quarters for his ignorance or tolerance of evil. But is this not because the holiness of his life and thought keeps him so close to his divine Master that he can only see good in all he gazes on? It is the eagle, ever steadfastly beholding the sun, that swoops down upon carrion, and thanks God for the meal. It is the purblind race of miserable men that turn fastidiously from wholesome and natural food. However this may be, it is undoubtedly no easy task to follow the royal bird in his dazzling flight through illimitable aethyr. Yet the attempt will avail us much; even if we can rise only some few feet above the ground, we may say, “something attempted, something done.” And as we grow bolder, we shall be more at ease in the new element, or even, like the sparrow on the eagle’s back, equal the splendid soaring of our princely pioneer. For those to whom much of Crowley is obscure, no better lamp can be found than this brilliant book of Captain Fuller. —The Seeker, circa August 1907 ______________________________

We must confess that our intelligence is not equal to the task of wrestling with this book. It is quite an unusual sort of book. “At first sight,” says the author, in the first sentence of his preface, “it may appear to the casual reader of this essay, that the superscription on its cover is both forward and perverse and contrary to the sum of human experience.” Which appears to be sane and intelligible enough until you read the superinscription, which is as follows:

V. V. V. V. V. I. N. T. A. 666 418

The whole being surmounted by certain mysterious symbols. “Contrary to the sum of human experience” is not quite how we should express it. Most of the volume appears to be devoted to an appreciation of the poetic works of a Mr. Aleister Crowley, whom Captain Fuller describes as “No vestal. . . . No mere milk-and-bun-walk, where we may rest and take our fill; for he has unstrung the mystic lyre from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and of Evil, singing old songs and new,” etc. We are also informed that “Crowley fairly puts his characters to bed, tucks them up, and does not blow the candle out with cryptic Morse-like dot and dash, leaving the imagination to wallow in the dark, intelligible to the baby mind of sucklings, and we admire him all the more for not doing so.” Concerning which we have nothing to say, except that we wonder why authors like Captain Fuller always send their books to the Clarion? —The Clarion, 13 September 1907 ______________________________

“The Star in the West,” by Captain J. F. C. Fuller (the Walter Scott Publishing Company, Limited), consists of a critical essay upon the works of Aleister Crowley, who is described as having “unstrung the mystic lyre of life from the tree of the knowledge of Good and of Evil, singing old songs and new, flinging shrill notes of satire to this tumultuous world, as some stormy petrel shrilly crying to the storm; or sweet notes of love, soft as the whispering wings of a butterfly.” Captain Fuller’s language is always picturesque, and those who have not read Crowley’s poems could not discover a more enthusiastic cicerone. He insists on the superabundance of the poet’s genius and the diversity of his form, points that find ample accentuation in the course of the work. Crowley has been eminently unconventional, and has not called a spade an agricultural implement. Captain Fuller declares that what Beardsley and Whistler did for art, Crowley is now doing for poetry, and he adds that his hero in now superseding Swinburne. —The East Anglian Daily Times, 5 August 1907 ______________________________

Happy the minor poet who can secure so exhaustive an examination of his writings as that contained in this extraordinary volume. If we adopt the author’s estimate, Mr. Crowley is no longer to be termed a “minor” poet, but stands in the ranks of the immortals. Captain Fuller, it is true, deals more in eulogy than in criticism, and would be a more convincing interpreter if he did not write as a Qabalist, an adept in ceremonial magic, occult Buddhism, and “all that sort of thing.” His knowledge is weird and remarkable, his ethics unfettered by the shackles of convention, and his style frequently eccentric, sometimes in doubtful taste, and sometimes, like that of his master, rushing onward in a torrent of bold and magnificent images. Here, for instance, is a piece of “fine writing” which, of its kind, is excellent, though its meaning we presume not to fathom:

O, Dweller in the Land of Uz, thou also shalt be made drunken; but thy cup shall be hewn from the sapphire of the heavens, and thy wine shall be crushed from the clusters of innumerable stars; and thou shalt make thyself naked, and thy white limbs shall be splashed with the purple foam of immortality. Thou shalt tear the jeweled tassels from the purse of thy spendthrift Fancy, and shalt scatter to the winds the gold and silver coins of thy thrifty Imagination; and the wine of thy Folly shalt thou shower midst the braided locks of laughing comets, and the glittering cup of thine Illusions shalt thou hurl beyond the confines of Space over the very rim of Time.

After two or three pages of this the reader may well echo the chapter’s concluding cry: “Wine, wine, wine!” The first half of Captain Fuller’s book is a tolerably sober and often penetrative elucidation of the meaning of Mr. Crowley’s fine poems. This we understand and like. It has certainly brought home to us more vividly the great beauty and insight of the poet’s work. But in the latter part of the book, consisting of one long chapter entitled “The New Wine,” and in which the philosophy of “Crowleyanity” is expounded at dire length, our admiration for Captain Fuller’s judgment is somewhat abated. “Aleister Crowley,” we are told, “is the artist Elias” of whom Paracelsus prophesied:

the marvellous being whom God has permitted to make a discovery of the highest importance in his illuminative philosophy of Crowleyanity, in the dazzling and flashing light of which there is nothing concealed which shall not be discovered. It has taken 100,000,000 years to produce Aleister Crowley. The world has indeed labored, and has at last brought forth a man. . . . He stands on the virgin rock of Pyrrhonic Zoroastrianism, which, unlike the Hindu world-conception, stands on neither Elephant nor Tortoise, but on the Absolute Zero of the metaphysical Qabalists. . . . And he shall be called “Immanuel”—that is, “God” with us, or, being interpreted, Aleister Crowley, the spiritual son of Immanuel whose surname was Cant.

The author must have felt a good deal better after writing that. It is claiming much for Mr. Crowley that he embodies and completes the highest philosophy of Hume, Kant, Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel; that Crowleyanity is the scientific illuminism which reconciles the vision of God with the hard facts of natural law. But if the reader accepts this, he had better do so on the authority of the interpreter rather than on an intelligent understanding of the message, for at this he will have difficulty in arriving. We frankly confess that this part of the exposition baffles our comprehension. The quaint symbolical frontispiece to the book is a sort of picture-puzzle to the uninitiated. Captain Fuller’s task has apparently been a labour of love, and he has certainly expended great pains and ability in dragging Mr. Crowley up the steep slopes of Olympus.

—The Literary Guide, circa 1907 ______________________________

“The Star in the West,” by Captain Fuller, is a critical essay on the poetical works of Aleister Crowley, and the name will sound familiar in the ears of any who pride themselves on having more than a bowing acquaintance with modern letters. Mr. Crowley has over thirty volumes to his credit, and the sheer art of his verse should rank him high amongst modern singers. He has, however, deliberately preferred to write for the few, and the course he has mapped out for himself includes the consideration of questions which the majority are content to shuffle into the background. Captain Fuller writes with a generous enthusiasm that it is pleasant to find in these degenerate days, but one wonders if he was the best guide along a very difficult path. His pen slips too readily into rhetorical glorification of his hero, and this kind of writing does not help us much to a critical appreciation of a poet’s work.

I here offer this work to my readers as a twisted clue of silk and hemp to guide them safely through the labyrinthine mysteries of poetry and magic, whose taurine crags hug the blue sky, amorous as the kisses of Pasiphae, across the Elysian fields of myrtle and asphodel . . . to the cool groves of Eleusis childlike dreaming in the bosom of silvery Attica by the blue Ægean Sea.

The volume is a curious mixture ranging from fine lyrical poetry to an exposition of “Crowleyanity” which Captain Fuller assures us begins where agnosticism and scientific Buddhism end. It will not please all tastes, not is it suitable for all, but verses like this—and there are scores as good in the book—are too rare to be the property of a few:

The spears of the night at her onset Are lords of the day for a while, The magical green of the sunset The magical blue of the Nile; Afloat are the gales In our slumberest sails, On the beautiful breast of the Nile.

—The Northern Whig, 10 August 1907 ______________________________

This work is called “a critical essay on the writings of Aleister Crowley.” Yet it is, in truth, far more than this, being a highly original study of morals and religion by a new writer, who is as entertaining as the average novelist is dull. Nowadays human thought has taken a higher place in the creation; our emotions are weary of bad baronets and stolen wills; they are now only excited by spiritual crises, catastrophes of the reason, triumphs of the intelligence. In these fields Captain Fuller is a master dramatist, and we have no hesitation in predicting that modern readers, weary of the sordid and tawdry tediousness of gutter realism and Utopia idealism, will find in this book a satisfaction of many a heartache. —What's On, circa August 1907 ______________________________

Aleister Crowley’s works are caviar to the general, and it does not seem likely that this critical essay upon them will serve in any way to popularize them. One of the points the writer makes is that they are written, not for the vulgar many, but for some discreet and understanding few, who can see through the veil of their egotistical expression to an esoteric meaning which they convey. Naturally, such a contention leads the exposition along a retrograde course, for a simple-minded man, whether in reading poetry or in any other business, can see as far through a milestone as can the most advanced aesthete; but this commentator proceeds to explain the known by the unknown, and, beginning by laying it down that Crowley is the greatest of the English poets since Swinburne, with some of whose works his own has traces of affinity, goes on by successive stages to a conclusion in which all human philosophies are merged into one culminating doctrine of mystical symbolism that finds its fittest expression in the lines of Crowley, here freely quoted in order to illuminate Saint Augustine and the Oriental yogis. All this falls in with the emblems on the title-page and cover of the book—the rose of the world, the flaming star, the disembodied wings, and all the rest of them, and suggests that the book must mean something very deep indeed. Perhaps it may. A prospective reader may be left to discover the Grand Arcanum for himself. Crowley seems to have found it, if his critic is to be believed, in the anthology of the Cabala and in New-Rosicrucianism, where, no doubt, it is as clear as mud. —The Scotsman, 18 July 1907 ______________________________

It is certainly not to be denied that Aleister Crowley’s works require elucidation if we are able to appreciate their mystical symbolism, though even with the help of Captain Fuller’s clever, and often brilliant, essay all may not arrive at an understanding, or at all events a sympathetic understanding, of the poet. The author would have us believe that what Beardsley and Whistler did for art, Crowley is to-day doing for poetry. This is the place in which Captain Fuller places him:—“It has taken 100,000,000 years to produce Aleister Crowley. The world has indeed labored, and has at last brought forth a man, Bacon blames the ancient and scholastic philosophers for spinning webs, like spiders out of their own entrails; the reproach is perhaps unjust, but out of the web of these spiders Crowley has himself twisted a subtle cord on which he has suspended the universe, and swinging it round has sent the whole fickle world’s conception of these excogitating spiders into those realms which lie behind Time and beyond Space. He stands on the virgin rock of Pyrrhonic-Zoroostrianism, which unlike the Hindu world conception, stands on neither Elephants nor Tortoise, but on the Absolute Zero of the metaphysical Qabalists.” —The Newcastle Daily Chronicle, 31 July 1907 ______________________________

Before I opened The Star in the West, by Capt. J. F. C. Fuller (Walter Scott. 6s. net.), I must confess never to have heard of Aleister Crowley. The present volume purports to be a critical essay upon his works. You are glad that an interpreter has come forward to assist you in the elucidation of them. If I can gather anything from the preface and forward it is the list of the names of Crowley’s books upon which this criticism is based. They have the merit of variety:, Aceldama; The Tale of Archais; Songs of the Spirit; Jezebel; An Appeal for the American People; Jephthah; The Mother’s Tragedy; The Soul of Osiris; Carmen Saeculare; Tannhäuser; Berashith; Ahab; The God-Eater; Alice; The Sword of Song; The Star and the Garter; The Argonauts; Goetia; Why Jesus Wept; Oracles; Orpheus; Rosa Mundi; Gargoyles; Collected Works, vols. i., ii., and iii. I cannot agree with Capt. Fuller’s estimate of any of the lines and passages which he quotes. Where they have any merit at all it is as cheap imitations of Swinburne. For the most part they are poor verse, showing neither originality not rhythmicality, expressing in commonplace phraseology the ravings of a mind like an absinthe drinker’s. They are not to be compared in merit either of music or word painting or illuminating knowledge with the poems of the late Frank Saltus, the elder brother of the novelist. In the matter of startling phraseology Capt. Fuller easily distances the writer of whose works his admiration is so chivalrous and so profound. The seven chapters of the book are christened “The Looking Glass,” “The Virgin,” “The Harlot,” “The Mother,” “The Old Bottle,” “The Cup,” and “New Wine.” I suppose that there is something at the back of it all, but it is far beyond my comprehension. —The Queen, 14 September 1907 |

|||||||||||||||||||||